Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

Est. 1976

Hips & Patellas

|

HIP DYSPLASIA is a common cause of

rear-end lameness in the dog. The problem lies in the structure

of the joint. The head of the femur (thigh bone) should sit

solidly and tightly in the acetabulum (cup). In hip dysplasia

loose ligaments allow the head to begin to work free. A shallow

acetabulum also predisposes to joint laxity. Finally, the mass

or tone of the muscles around the joint socket is an important

factor.

Tight ligaments, a broad pelvis with a well-cupped acetabulum,

and a good ratio of muscle mass to size of bone, predispose to

good hips. The reverse is true of dogs who are likely to develop

the disease. Environmental factors, including weight and

nutrition of the puppy and rearing practices figure into the

final outcome. Keeping a growing puppy lean and on a good diet

will greatly mask and may even prevent the symptoms of hip

dysplasia.

Above are examples of hip x-rays of two different Cavaliers. If

you compare the two you can see that the hip sockets on the

right x-ray are not as deep as those on the left x-ray,

therefore the femoral heads do not sit as deeply into the

sockets—more of the femoral head is left out of the socket.

Also, in the dysplastic x-ray, you can see the circled hip is

much worse than the other hip. The end of the femoral head is

already worn down. Because of stress, the area pointed to behind

the femoral head has filled in so much the indentation is nearly

gone. Compare this to the other three hips that have good

indentation behind the femoral head. NOTE: the dog with the

dysplastic hips showed NO signs of hip dysplasia when walking

or running. The x-ray was taken only because the owner wanted to

make sure the dog did not have hip dysplasia before it was bred.

Since the dog does have hip dysplasia, the breeder decided not

to breed the dog. Also, BOTH parents are OFA clear of hip

dysplasia, and so is the one other sibling whose hips have been

x-rayed and sent to OFA.

Hip dysplasia is a moderately heritable condition. It is more

likely among littermates having a dysplastic parent, but even

dogs with normal hips can product dysplastic pups.

However—consistently breeding unaffected dogs WILL reduce the

incidence of hip dysplasia, especially if the hip status of

littermates is taken into consideration.

According to OFA statistics, approximately 10-11% of all

Cavaliers develop hip dysplasia by 2 years of age. Please note

that this figure is considerably lower than the true incidence

as the vast majority of breeders do NOT send in x-rays that show

obviously dysplastic hips. The widely accepted guess is that the

incidence is probably about twice as high as what the OFA

statistics show. Again, this is a developmental defect. Puppies

are NOT born with hip dysplasia. Some dogs with x-ray evidence

of even severe hip dysplasia show NO clinical signs (no pain or

lameness), so the disease may remain entirely unsuspected unless

an x-ray is taken to check for it.

OFA uses the following method of classifying hip dysplasia. A

clear x-ray of the hips is taken and sent to OFA for evaluation.

Preliminary x-rays (taken before the dog is age 2) are evaluated

by one radiologist. Permanent x-rays (taken after the dog is 2

years old) are evaluated by three radiologists who have to come

to an agreement on the status of the hips. Hips declared free of

hip dysplasia are assigned either an Excellent, Good or Fair

rating. There is a Borderline Conformation/Intermediate

classification in which they normally ask that the dog be

x-rayed again at a later date for re-evaluation. Hips that are

dysplastic are rated as Mild, Moderate or Severe. OFA suggests

that only dogs FREE of any signs of hip dysplasia in the x-rays

should be used for breeding.

Below are hip x-rays of Cavaliers showing most of the grades of

classification. I don’t have a copy of a Borderline or a Severe.

You can find examples from other breeds online if you are

interested. You can easily see in each x-ray how there is less

and less coverage of the head of the femur (the femoral head—the

round ‘ball’ at the ‘top’ of the leg bone) and the acetabulum

(the ‘cup’ where the femoral head sits) gets more shallow as the

status of the hips declines until they barely overlap at all. In

a severe there is basically no overlapping whatsoever.

PennHIP uses an entirely different way of evaluating hips. They

have the vet take 3 different x-rays in 3 different positions to

check for laxity of the hip joints. A number is assigned to each

hip stating the amount of laxity found. PennHIP then publishes

the *average* hip scores for that particular breed. They suggest

that only dogs that have laxity scores in the *better* half

should be used for breeding. Obviously, although the aim is at

improving the hip status of offspring, some dysplastic dogs may

be able to be used for breeding under the PennHIP approach,

especially in breeds prone to a lot of hip dysplasia. This is a

more controversial approach, but their hope is that laxity is

the prime reason for the development of hip dysplasia and using

dogs with the lower laxity scores may possibly bring about

improvement in the breed more quickly.

Treatment for hip dysplasia is directed at relieving pain and

improving function by giving aspirin or one of the newer

products used in the treatment of degenerative joint disease. If

pain cannot be controlled, there are surgical procedures which

may relieve pain and improve function in some individuals.

For more information on hip dysplasia, please see some of the

following websites:

www.ofa.org/

www.vet.upenn.edu/pennhip/

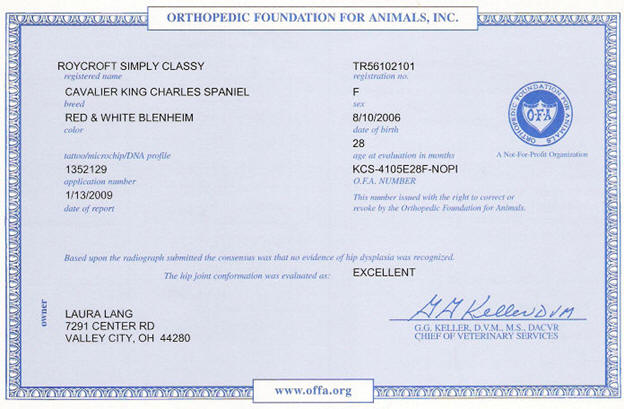

The following are the only acceptable result forms for hip

dysplasia in the USA:

Below is the OFA Hip Clearance Form

NOTE O.F.A. NUMBER ON FORM

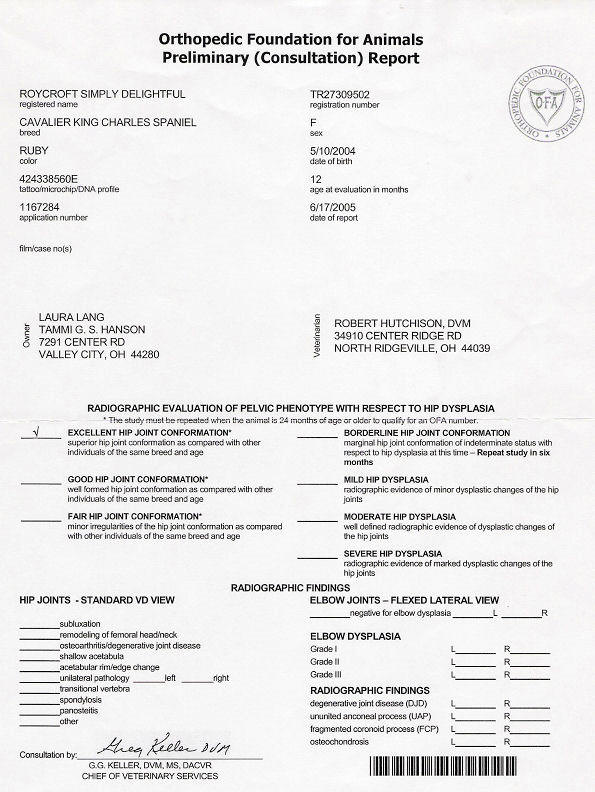

As an interesting comparison, the following is a picture of the

x-ray of the same dog, this time submitted to OFA for

evaluation. OFA evaluated her hips as *Fair*.

PATELLAR LUXATION or dislocating

kneecap(s) can be inherited, or acquired through trauma.

It occurs sporadically among Toy breed dogs, although it can be

found in large breeds.

In dogs the patella is a small bone which protects the front of

the stifle joint; it is the counterpart of the kneecap in humans.

It is anchored in place by ligaments, and slides in a groove in

the femur.

Conditions which predispose to patellar luxation are: a

shallow groove, weak ligaments; and mal-alignment of the tendons

and muscles that straighten the joint. The patella may

slip inward (medial luxation) or outward (lateral luxation).

Luxating patellas in toy breeds are most commonly found to

luxate medially. Lateral luxation is most commonly caused

by trauma, although in some cases it can also be inherited.

The signs of patellar luxation are difficulty straightening the

knee; pain in the stifle; and a limp. Often a dog with

patellar luxation will look somewhat stiff in that leg because

the dog is attempting to use muscles to *lock* it so the patella

won't move around as much.

The diagnosis is confirmed by a regular veterinarian who

manipulates the stifle joint and is able to push the kneecap in

and out of position without excess force.

There are 4 grades of patellar luxation:

(1) Intermittent patellar luxation causing the limb to be

carried occasionally.

(2) Frequent patellar luxation which, in some cases, becomes

more or less permanent.

(3) The patella is permanently luxated with torsion of the tibia

and deviation of the tibial crest of between 30 degrees and 50

degrees from the cranial/caudal plane.

(4) The tibia is medially twisted and the tibial crest may show

further deviation medially with the result that it lies 50

degrees to 90 degrees from the cranial/caudal plane.

Grades (1) and (2) can often be controlled by keeping the dog

lean, on a good diet (supplements may help as well), and not

allowing excessive jumping. A Grade 2 can tighten to a

Grade 1 and often a Grade 1 can tighten until there is no

patellar luxation at all. They can also get worse.

Grades (3) and (4) nearly always need surgery to deepen the

groove and/or realign or tighten the ligaments.

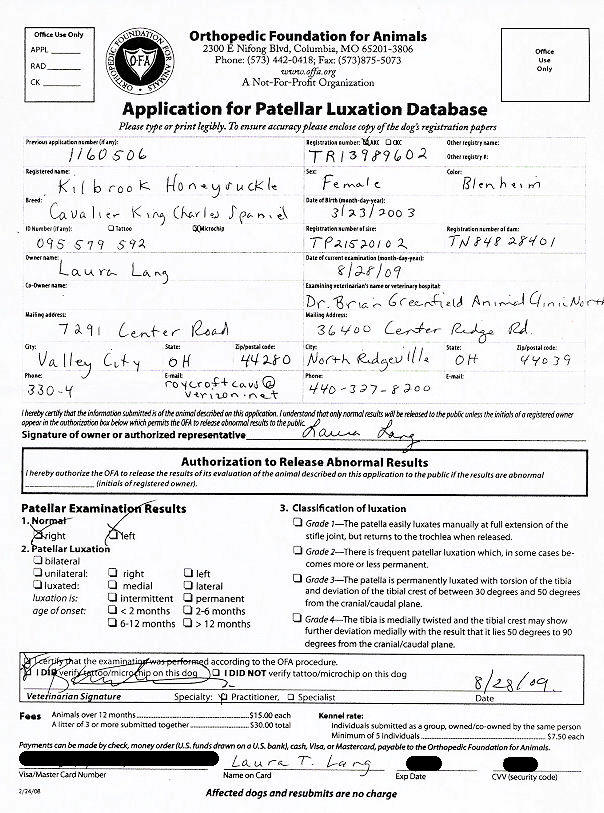

Any licensed veterinarian can manipulate and check for patellar

luxation. X-rays are not necessary.

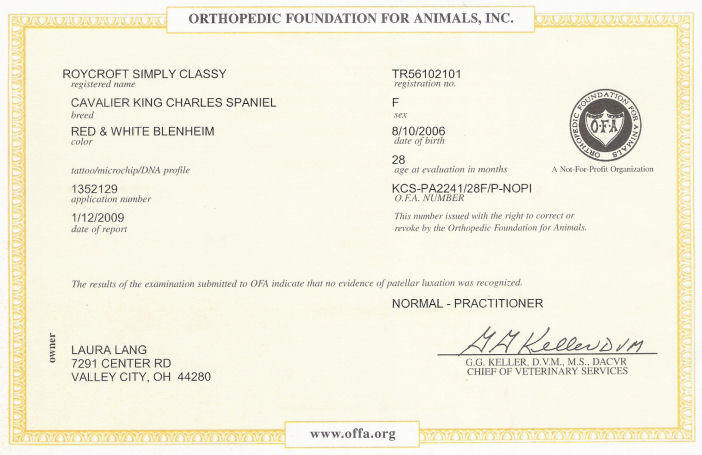

NOTE THE O.F.A. NUMBER ON FORM |

Copyright 2023 Roycroft Cavaliers

No part of this site may be copied or reproduced without written permission.